About us

What we do, and the story behind it.

What we do

We help tech companies recapture the innovative mojo they had as a startup.

Why it matters

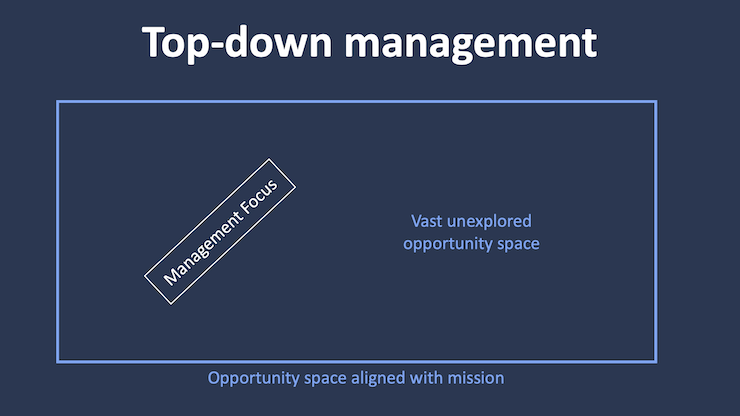

As a manager, you don’t have all the answers.

You need employees to take initiative in solving the company’s challenges.

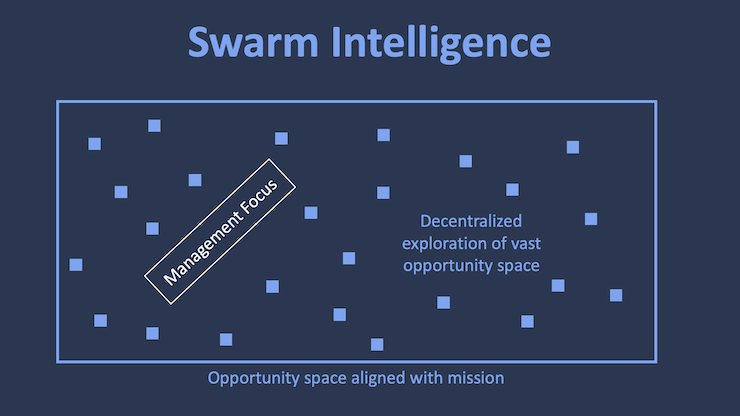

When everything has to come from you, your team misses out on the swarm intelligence that makes startups so nimble.

How we’re different

We go in and launch a skunkworks program to open up a second engine for innovation. This lets employees take on experimental projects to help the company succeed. You go from top-down to swarm intelligence in 90 days.

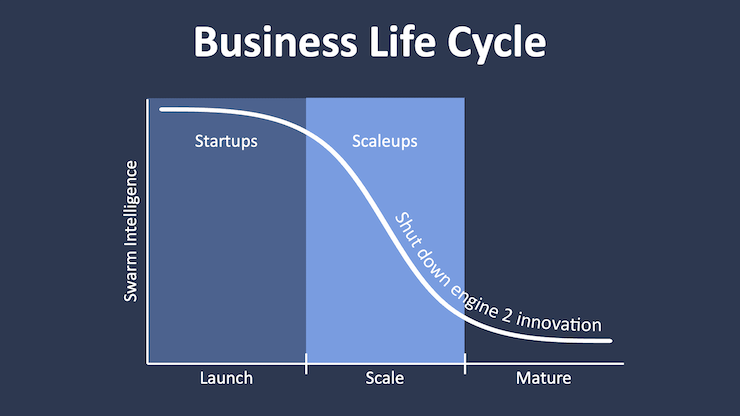

This second engine is what you find in startups. But it gets lost when companies scale and mature.

This isn’t Google’s 20% time. The second engine comes entirely from extra productivity, with zero impact to official projects and schedules.

Founder’s story

Jim Verquist, Founder

Hello, I’m Jim. Here’s the story of how this all started.

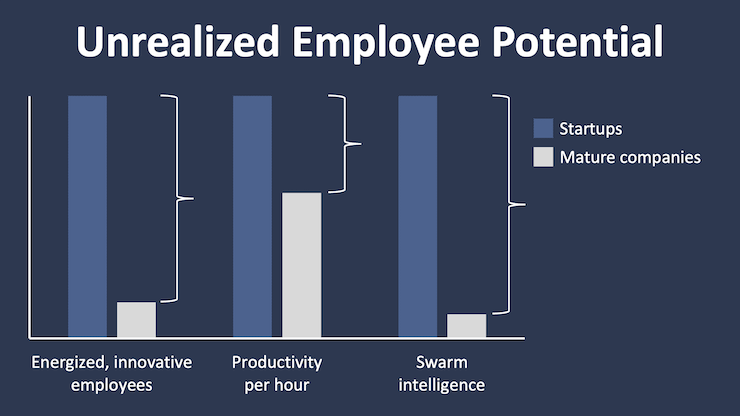

I did 3 Silicon Valley startups. Startups are the polar opposite of mature companies in how they innovate. Startups are all about entrepreneurial initiative and decentralized innovation. Mature companies are all about top-down decision-making and centralized innovation. I have always rejected the idea that it has to be this way.

Before Silicon Valley, I served 4 years in the U.S. Marine Corps. The Marine Corps is not exactly a bastion of innovation. It’s hard to imagine a more top-down, do what you’re told and only what you’re told organization in the world. Yet despite this, I found a way to innovate. Even better, I was the lowest ranking person in the entire department. One day I bumped into a problem that I thought was crazy. I could have swept it under the rug and forgotten about it. That’s what people in my role had been doing for 30 years. After all, when you bump into a problem that isn’t your fault, but you might be blamed anyway, you don’t normally run to tell your commanding officer about it. Not if you can avoid it. You’re more likely to get into trouble than to win accolades. But I decided I couldn’t just ignore it. It was causing real problems and hurting real people. I wanted to figure out what was going on and find a solution. So I quietly started working on it. I still did my regular job. But I also worked on my unofficial skunkworks project, whenever I could free up some time. Five months later I had revamped the process and fixed the problem. My commanding officer learned what I had done, and I was awarded the Navy Achievement Medal for innovation leadership. The highest non-combat medal awarded to junior enlisted personnel.

After Silicon Valley, I got my MBA and went to work for mature companies. My idea was to bring an entrepreneurial approach to change+innovation. Less top-down. More nimble. The way it works in startups. This turned out to be very successful. I led a turnaround at Millennium, and a Fast Strategy transformation at Best Doctors. But I wanted more. These projects were focused on decentralized execution of the proven business model. What I really wanted was the decentralized innovation you find in startups.

So I started reading everything I could find on Freedom-Based Management Models. The idea behind these models is simple. Wherever you have managers, you have bureaucracy. Since bureaucracy kills innovation, you need to get rid of all the managers and create truly self-managed companies. The often touted success stories include WL Gore, Semco, Morning Star, FAVI, and Valve. Gary Hamel laid out the vision succinctly in his Harvard Business Review article, “First, Let’s Fire All the Managers.”

My problem with this vision is it didn’t seem at all realistic. There was no way this model was going to take over the world. Most of the companies that tried self-management couldn’t make it work. Even Zappos under Tony Hsieh failed to make it work. And the “success stories” were seldom what they seemed.

For all the bad press bureaucracy gets, it turns out to be incredibly good at reliable, efficient execution of a proven business model. Since that is the primary focus of every successful business, bureaucracy has a lot going for it. The problem isn’t bureaucracy. The problem is the lack of decentralized innovation to go alongside bureaucracy.

I realized that the unofficial skunkworks project I did in the U.S. Marine Corps might be a solution. Companies could keep their management systems exactly as they are. But also enjoy all the benefits of decentralized innovation. The challenge was how to get enough employees to do this. In startups, everyone does this. But in mature companies, not more than 1 in 1,000 employees launch unofficial skunkworks projects. They may want to. But it feels too risky. So they do nothing. The potential is there. But it rarely turns into anything more than an idea in someone’s head. Yet take those same employees and put them in a startup or on a skunkworks team, they will suddenly be innovative. Just like everyone else around them. The question was how to unlock these dynamics on regular teams in mature companies.

So I set out to find a solution. Find a way to go into any company and get the entrepreneurial initiative you find in startups.

The solution is built into the most famous storytelling model in the world. The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell. It explains why most employees do nothing when they bump into a problem or opportunity. Even though they want to. They get stuck in the “Refusal of the Call.” In the Hero’s Journey, we’re dealing with an unlikely hero. Someone who isn’t supposed to save the day. Facing a daunting challenge. Up against terrible odds. Full of fear and insecurity. In rare cases, they can muster the courage on their own. Set out on the journey into the unknown. But in most cases, they need some help. To use a Star Wars analogy, you need an Obi-Wan Kenobi for the Luke Skywalkers in the company (unlikely heroes of ANY gender). Without an Obi-Wan Kenobi, the Luke Skywalkers never set out to save the universe. Even when the CEO makes it official company policy to allow unofficial skunkworks projects, it feels too risky without a catalyst.

If you want employees to take initiative in mature companies, you need an Obi-Wan Kenobi. Managers cannot be the catalyst. That is the epiphany that lets you go from top-down to swarm intelligence in 90 days. No coaching or training needed.

It turns out, 3M happened upon this model in the 1920s. Decades before their famous 15% rule. It transformed 3M from a 23-year-old sandpaper company into one of the most innovative companies on the planet. Dick Drew was 3M’s original unofficial innovator, and he played the role of Obi-Wan Kenobi. He inspired an entire generation of innovators at 3M. They created breakthrough after breakthrough. Unfortunately, 3M didn’t understand the model. After Dick Drew retired, 3M’s unofficial skunkworks projects disappeared too. Later 3M launched their 15% rule. But it has never been very successful in creating breakthroughs. It violates the dynamics that make unofficial skunkworks projects so successful.

That’s the story behind this new skunkworks program. Unofficial skunkworks projects have created more billion-dollar breakthroughs than Bell Labs and Xerox PARC combined. It’s how Ken Kutaragi created the PlayStation at Sony. Gary Starkweather created the laser printer at Xerox. Shuji Nakamura created LED lighting at Nichia. Gary Klassen created BlackBerry Messenger at RIM. And so much more.

Now we’re bringing unofficial skunkworks projects to tech companies around the world. For managers who want to recapture their company’s innovative mojo.